By John Ikani

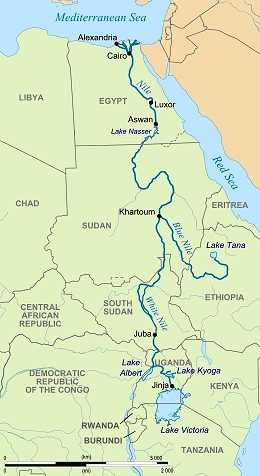

The life of millions of Africans depends on the Nile, the continent’s longest river, which runs from Uganda to Egypt, and whose water basin covers 10% of the continent.

At more than 6,600 kilometres long, the Nile basin extends to 11 countries, including Tanzania, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Egypt – where hundreds of heads of state gathered to attend the COP27 climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Frighteningly, the world’s second-longest river has come under strain in the past 50 years and currently face grave threats from its source to the sea. Its flow has dropped from 3,000 cubic meters per second to 2,830 cubic meters in just half of a century, with experts predicting a 75% reduction in the river’s flow by 2100!

It all begins with the source

Lake Victoria is the Nile’s main source of water. However, the lake is currently in danger of disappearing due to evaporation and changes in the tilt of the Earth’s axis.

With multiple droughts in East Africa occasioned by human-driven climate change, there is little to no rain to replenish the Lake which also suffers increased water use in the catchment area.

Lake Victoria could disappear entirely within the next 500 years, according to a study by British and American scientists based on geological data from the last 100 000 years.

Pollution, exploitation and eroding deltas

What’s left of Lake Victoria with tits and bits of accumulated rainfall in the Nile basin flow north to Egypt amid grave threats from pollution, and human exploitation.

As though pollution in the entire Nile basin was not enough problem, in Ethiopia, the government of Addis Ababa is exploiting what’s left of the Nile to generate electricity for more than half of Ethiopia’s 110 million people.

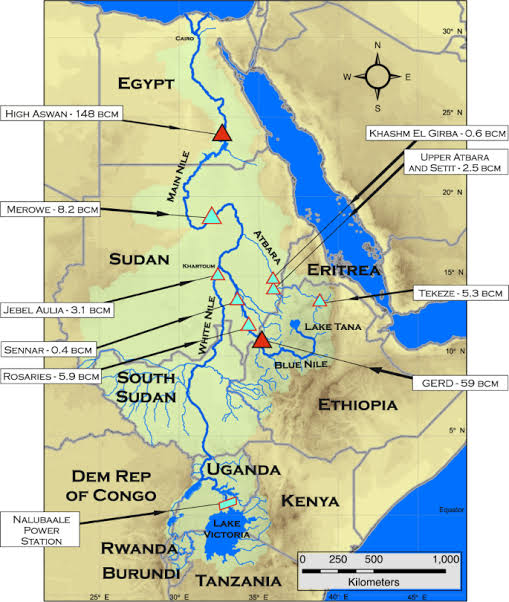

Begun in 2011, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile — which joins the White Nile in Sudan to form the Nile — already holds nearly a third of its 74-billion-cubic-metre capacity.

According to Addis Ababa, the GERD mega-dam project is the biggest hydroelectric project in Africa. Similarly, more than half of Sudan’s power comes from the Nile while 80% of Uganda’s electricity is generated from the same river.

On eroding deltas

Up north in Egypt where an already weakened Nile has its deltas, there’s little to no fresh water draining into the Mediterranean Sea. In fact, the Nile delta is gradually sinking into seawater with estimates projecting that nearly 3,000 square kilometres of the delta will be sunk by 2100.

The delta’s subsidence can be traced to many factors. One key contributor is Egypt’s upstream Aswan High Dam, built in the 1960s, which has reduced the amount of sediment that reaches the delta by more than 98%. Unable to replenish sediment lost to erosion, the delta has been gradually starved of its fertile mud.

Simultaneously, over the past 30 years, Egypt has been pumping groundwater for agricultural, industrial, and urban use at an exponential rate, causing large areas to subside. In addition, Egypt has rapidly become Africa’s second-largest producer of natural gas, extracting much of that fuel from the thick layers of sand and shale underlying the delta and exacerbating subsidence.

Impacts

A drying Nile leaves the 10 countries that rely on the river for their crops and power in dire straits.

With little to no feeder rains, the dams are set up for underperformance. Also, outlets from the reservoirs come without the much-needed silts required by farmers that live on the banks of the Nile to grow cucumbers, aubergines, potatoes among other crops, thereby catalysing famine.

The situation is particularly worrisome in Egypt where 41% of the population—roughly 95 million people, live in the fertile Nile Delta (about 2% of Egypt’s total area).

These communities are under threat as the Mediterranean eats away between 35 and 75 metres of the Nile Delta every year, making what was once a bread basket one of the most vulnerable places on the planet.

If the sea level rises even by a metre, a third of this intensely fertile region could disappear, the UN fears, forcing nine million people from their homes.

What is being done to address the issue?

It may seem as though countries in the Nile basin have accepted the foreseeable inevitability of what lies ahead for the river, and are scrambling to capture what’s left of its flow.

They are also on the lookout for alternatives like Egypt which is leveraging its proximity to the Mediterranean to build a giant belt of lakes and parks deep in the desert. Creators call it the “Green River.”

More so, in hosting this year’s climate talks, Egypt has made it clear that COP27 will focus primarily on wringing climate finance out of the rich countries that are most responsible for climate change, as opposed to seeking possible solutions to Nile’s woes.