By Eswar Prasad

The future of retail and peer-to-peer payments is undoubtedly digital. As the use of cash plunges around the world, central bank digital currencies are an inevitable part of this transition.

Most central banks are bowing to this reality, either experimenting with or preparing the ground for CBDCs — as instruments for broadening financial access, increasing payment system resilience and ensuring monetary sovereignty. Even as these digital tokens gain momentum, however, the case for them has weakened.

What has changed?

In the first place, the landscape looks less promising in practice than it did in theory a couple of years ago. China, Brazil and India are undertaking trials but face scant demand for their CBDCs, as they already have excellent digital payment systems.

Sweden’s Riksbank has concluded a multiyear pilot but a parliamentary committee has found no pressing need for an e-krona.

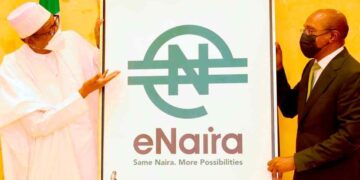

Nigeria’s eNaira has been a flop, although recent cash shortages have increased its usage. The official response to the financial distress precipitated by Silicon Valley Bank’s failure in the US has also indirectly highlighted concern that retail CBDCs could deplete bank deposits.

A simple safeguard against disintermediation of banks is to limit the amounts that can be held in CBDC digital wallets. But as evident from the lifting of deposit insurance caps when depositors lost confidence in some banks, a limit on CBDC digital wallets might prove difficult to sustain at a time of crisis and could precipitate a banking meltdown.

Conspiracy theories are also heating up, built on legitimate concerns about the privacy implications of CBDCs. Far-sighted Florida governor Ron DeSantis has pre-emptively banned the use of as-yet nonexistent digital dollars in his state.

But, given their inevitability, what principles should guide the next phase of CBDC development?

First, clarity about the value proposition for users. In many countries, there simply isn’t demand for central bank money for retail payments. China’s payment giants (Alipay, WeChat Pay) and India’s Unified Payments Interface have made low-cost digital payments easily and widely available.

In the US, the Federal Reserve’s instant payment service FedNow will increase the system’s efficiency and resilience. Still, a well-designed CBDC could play an incremental role in catalysing payments innovation. Other advantages, such as the ability to facilitate payments using near-field communication even when cellular and wireless networks are down, could also be played up.

Second, design choices could make the balance of risks more favourable. Central banks would provide the digital tokens and commercial banks custodial services for CBDC digital wallets in the two-tier system that underlies most CBDC experiments.

A fee schedule could discourage large transfers to the wallets, while regulatory changes make it easier for banks to cope with shifts from their deposit accounts to CBDC wallets without precipitating liquidity shortages.

New cryptographic technologies can help alleviate privacy concerns and make it possible to verify the bona fides of users without compromising transactional privacy.

Third, the introduction of a CBDC should be determined by capacity and institutional constraints. Nigeria forged ahead without adequate infrastructure to support the eNaira, limiting its adoption. There is some advantage to waiting and learning from the experiences of others.

The notion that a successful digital renminbi would set a global standard and shake the dollar’s dominance is far-fetched. The US has made its potential CBDC design available as open-source code and it is unlikely any significant country will adopt the digital renminbi’s architecture simply because it was ahead in the game.

For smaller countries with weak central banks, quicker adoption would help maintain sovereignty over domestic payments. A CBDC by itself will not make up for a central bank’s lack of credibility, though. Fourth, there is a strong case for wholesale CBDCs, for interbank payment and settlement within and across national borders, to reduce frictions in international payments.

Retail CBDCs do have advantages over cash, broadening the tax base and limiting the use of central bank money for illicit activities, and even over private digital payment systems — lower cost, easier access, interoperability across platforms. CBDCs might be inevitable as cash disappears, but central banks need to structure them to make them worthwhile and leave the design choices flexible enough to incorporate technological changes that mitigate the risks.

The writer is a professor at Cornell, senior fellow at Brookings, and author of ‘The Future of Money’