By John Ikani

The Nigerian Government has firmly opposed the proposition to phase out fossil fuels, a hot topic at the ongoing United Nations Climate Change Summit in Dubai, UAE.

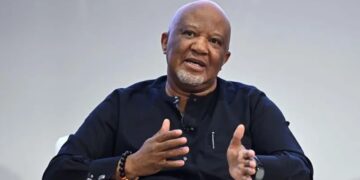

”It is unacceptable to ask Nigeria or Africa to phase out fossil fuels,” stated Ishaq Salako, Nigeria’s Minister of State for Environment, likening the demand to urging a sick patient to breathe without life support. Nigeria’s economy heavily relies on fossil fuels, specifically petroleum.

Fossil fuels contribute to over 75 per cent of GreenHouse Gas (GHG) emissions, the primary cause of climate change. The ongoing Climate Change conference necessitates consensus among participating parties.

In the initial draft of the Global Stocktake (GST) on Sunday, nations were urged to phase out fossil fuels, facing resistance from OPEC and Nigeria.

Gabriel Aduda, Permanent Secretary at Nigeria’s Ministry of Petroleum Resources, expressed his disapproval on X (former Twitter), stating that certain sections of the draft COP28 GST Negotiations were a firm “NO – NO.” He emphasized the importance of fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, for sustainable development, urging a focus on emission reduction rather than phasing them out.

After negotiations and modifications on Monday, the text’s language was adjusted to read, ”Reducing both consumption and production of fossil fuels, in a just, orderly and equitable manner so as to achieve net zero by, before, or around 2050 in keeping with the science.”

Scientists argue that achieving the 1.5-degree Celsius global temperature limit, as outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement, is impossible without ultimately eliminating fossil fuel usage.

On Tuesday, Mr Salako countered the scientific perspective, stating, ”You cannot do science without looking at the socio-economic implications.” He insisted that if developed nations push for a fossil fuel phase-out, they must ensure socio-economic guarantees for less-privileged countries like Nigeria.

Mr Salako asserted that countries have alternatives, and net zero emission pathways must consider each nation’s differentials and local context.

Nigeria, as Africa’s largest oil producer, heavily relies on oil and its products for its economy.

”The developed world has adopted what suits them, and we do not agree that is total science,” Mr Salako concluded.

In alignment with the minister’s stance, Chukwumerije Okereke, a Nigerian climate change expert, emphasized the need for an equitable and fair approach to fossil fuel phase-out, considering the country’s economic challenges.

”Nigeria is in a double bind when it comes to the fossil phase-out issue,” he noted, recommending a rapid transition from fossil fuels while allowing for the short to medium-term use of fossil fuels, especially gas, as a transitional measure.

Ruth Soronnadi, a human rights lawyer, attributed Nigeria’s resistance to political and economic realities, stressing the importance of justice and human rights in climate change decisions.

”The fossil fuel phase-out is an opportunity to wean Nigeria from her petroleum dependency and enable her to explore other renewable energy options,” she suggested, advocating for holding oil, coal, and gas companies accountable for the harm they cause during the transition process, particularly to vulnerable communities.