By John Ikani

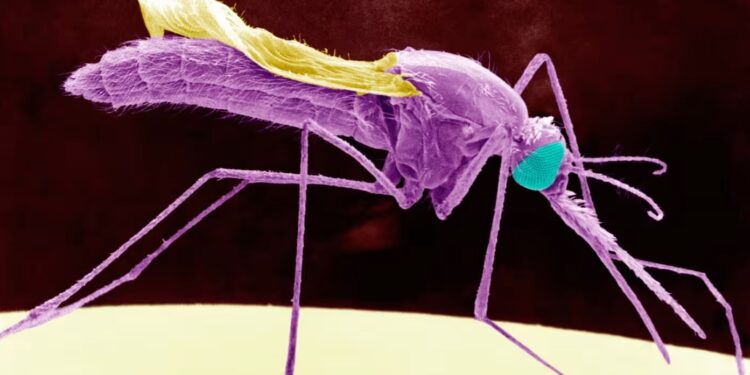

Djibouti has launched a pilot program using a novel weapon in the fight against malaria: genetically modified mosquitoes.

The “friendly” male mosquitoes, developed by Oxitec, a UK biotech company, are the male Anopheles stephensi, specifically engineered to be “friendly.” They cannot bite or transmit diseases like malaria, but they do carry a special gene that disrupts the development of female offspring.

A Targeted Approach

The key lies in the fact that only female mosquitoes bite and transmit diseases like malaria.

The lab-created males, belonging to the Anopheles stephensi species, are designed to seek out and mate with wild females.

When they do, the self-limiting gene prevents any female offspring from reaching adulthood.

Over time, this should significantly reduce the mosquito population and curb the spread of malaria.

Innovation for a Pressing Need

This is the first release of its kind in East Africa, and the second on the continent.

Djibouti was once close to eliminating malaria, but the arrival of the invasive Anopheles stephensi mosquito in 2012 reversed those gains.

Cases skyrocketed from a handful to a staggering 73,000 by 2020.

The resilient mosquito thrives in urban areas, bites both day and night, and resists traditional insecticides.

Building on Global Success

The technology behind these friendly mosquitoes has a successful track record.

Over a billion such insects have been released worldwide since 2019, with deployments in Brazil, the Cayman Islands, Panama, and India demonstrating their effectiveness.

Safety First

While genetically modified organisms (GMOs) often raise concerns, Oxitec emphasizes the rigorous safety measures in place.

Extensive research has shown no adverse environmental or human health impacts after over a decade of releases.

The self-limiting gene is not present in the mosquito’s saliva, so even bites pose no risk.

Community Support and Looking Ahead

The compact size and predominantly urban landscape of Djibouti make it an ideal testing ground for this innovative approach.

Local residents, like malaria survivor Saada Ismael, are eager to see if these friendly mosquitoes can turn the tide.

The initial success of the pilot program could pave the way for larger field trials and potentially widespread deployment by next year.

This technology offers a promising new weapon in the global fight against malaria, a disease that claims an estimated 600,000 lives annually, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing the brunt of the burden.