By Lucy Adautin

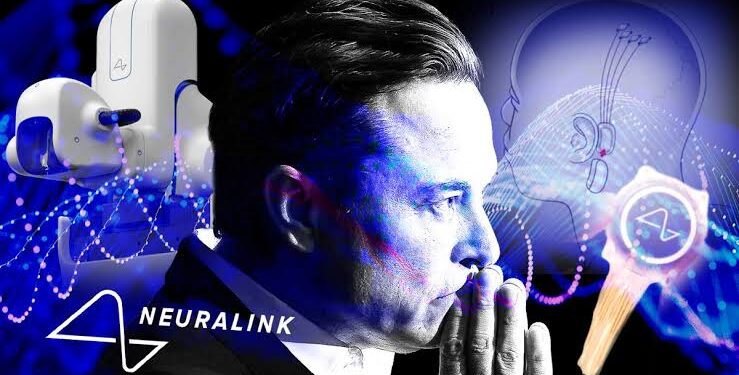

Elon Musk’s Neuralink achieved a significant milestone this week by implanting its brain-computer interface into a human for the first time.

Musk shared on his social media platform X that the recipient is “recovering well,” and early results indicate promising neuron spike detection, the device’s ability to detect brain cells’ electrical activity.

Elon Musk’s vision for Neuralink involves each wireless device housing a chip and over 1,000 ultra-thin, flexible conductors. These are delicately inserted into the cerebral cortex by a surgical robot, where the electrodes register thoughts associated with motion.

Musk envisions an app that will eventually translate these signals, enabling individuals to control computers simply by thinking. Musk has described this potential as akin to Stephen Hawking communicating faster than a skilled typist or auctioneer—an ambitious goal for the first Neuralink product, which he named Telepathy.

He said “Imagine if Stephen Hawking could communicate faster than a speed typist or auctioneer. That is the goal.”

The US Food and Drug Administration had approved human clinical trials for Neuralink in May 2023. And last September the company announced it was opening enrollment in its first study to people with quadriplegia.

Monday’s announcement did not take neuroscientists by surprise. Musk, the world’s richest man, “said he was going to do it,” says John Donoghue, an expert in brain-computer interfaces at Brown University. “He had done the preliminary work, built on the shoulders of others, including what we did starting in the early 2000s.”

READ ALSO: Nigeria: CBN Raises Interest Rate To 24.75%

Neuralink’s original ambitions, which Musk outlined when he founded the company in 2016, included meshing human brains with artificial intelligence. Its more immediate aims seem in line with the neural keyboards and other devices that people with paralysis already use to operate computers. The methods and speed with which Neuralink pursued those goals, however, have resulted in federal investigations into dead study animals and the transportation of hazardous material.

Musk has a habit of suggesting big things but providing little detail, notes Ryan Merkley, director of research advocacy at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. “This is maybe the biggest example of that” because there’s no information available about the person who received the implant or their medical condition, Merkley points out. “Depending on the patient’s disease or disorder, success can look very different.”

Are there limits to what a brain-computer interface can offer? Is it beyond the motivation that Musk has stated? Do we still have that dream of what folks were talking about 25 years ago? are some questions people ask.