By Olusegun Adeniyi

I doubt if there is any Nigerian on WhatsApp who has not watched the short video clip of the Nigeria Customs Service (NSC) officer beating his chest about successful negotiation with bandits in Dutsima local government area of Katsina State. Surrounded by his men and a battery of reporters, he said: “We are not working for only Customs, we are working for the nation and for you people (the reporters). I sacrificed my life to go to Dutsima to enter the bush where the bandits are. If I tell you last time we were in contact with them to the extent that they were a little bit friendly with us. We seized 37 bags of rice, they said if we have to go, they have to take seven bags. We gave them seven bags to save our lives, so you see the risk I took.”

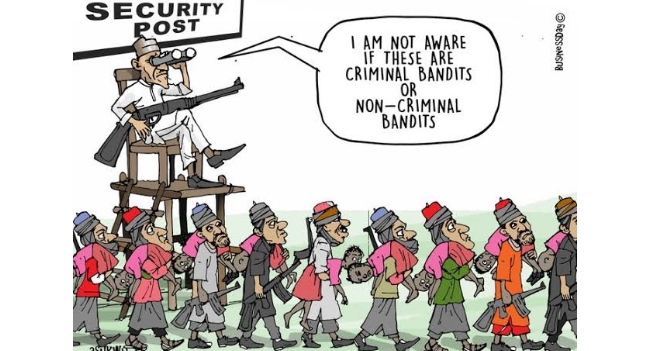

It is bad enough that a senior law enforcement official would publicly admit ‘paying taxes’ to criminals but worse is that he could not understand the implication of his action. Or maybe he did! Perhaps he has been told that bandits are a special breed of Nigerians since the current administration appears to have embraced Sheikh Ahmad Gumi’s Doctrine that they should be pacified and pampered rather than brought to justice. Even the National Assembly must have sensed a reluctance to tackle the challenge before passing a resolution calling on President Muhammadu Buhari to designate bandits and their sponsors as terrorists. Governor Nasir El-Rufai of Kaduna State would add that he had made several such pleas to no avail. “We have written letters to the federal government since 2017 asking for this declaration because it will allow the Nigerian military to attack and kill these bandits without any major consequences in international law,” he said.

Let’s be clear. I do not believe that the change in nomenclature will make any difference. Besides, banditry is largely driven by a transactional ethos and not backed by any political or religious ideology. To that extent, whatever may be our misgivings about Gumi’s role (and I am very suspicious of him), he is making a good point about the danger of designating these bandits as terrorists. But in the light of convenient excuses from some senior federal government officials on this vexatious challenge, it is difficult to fault the insinuation that this administration operates by some Orwellian Code: All criminals are equal, but some are more equal than the others.

Last Saturday, hundreds of women from Tsafe local government of Zamfara State (some with their children and belongings) blocked Gusau-Kaduna road to protest persistent attacks by bandits who invade their communities to kill, maim, rape and cart away their possessions. And on Monday, Daily Trust reported that despite the implementation of the Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) linkage to National Identification Number (NIN) policy on which the Minister of Digital Economy, Isa Pantami, was making a song and dance earlier in the year, kidnappers and bandits are still deploying mobile phones with SIM cards to demand huge ransoms from families of their victims. Quoting a report by the West Africa Network for Peace Building (WANEP), the paper reported that “496 civilians and 87 security personnel were killed as a result of various attacks by armed groups across the country in the month of September. Such attacks are usually planned through communication among bandits’ groups.”

Beginning in 2012 when 52 persons were brutally murdered in Zurmi in Zamfara State, we have continued to witness a harvest of deaths. On 7th April 2014, at least 112 persons were killed in a single attack on Yar Galadima village in Maru Local Government and just a few months later, 48 people were murdered after marauders on motorbikes entered a village called Kizara before dawn. Since then, hundreds of communities have been invaded by these outlaws who go by the fanciful name of ‘bandits’, killing innocent villagers and raping the women. All we hear from authorities are stories. On 8th April 2019, then Minister of Defence, Mansur Dan Ali claimed that some highly placed Nigerians, including traditional rulers, “were identified as helping the bandits with intelligence to perpetuate their nefarious actions or to compromise military operations.”

Although this madness of banditry began in Zamfara, it has since spread to Katsina, Kaduna, Sokoto and Kebbi with the North-west now practically at the mercy of killer-gangs. In another major report yesterday, the Daily Trust detailed how levies are being imposed on residents of many communities in Sokoto State by bandits who demand payment before next Friday or face brutal attack. Communities asked to pay N400,000 each include Attalawa, Danmaliki, Adamawa, Dukkuma, Sardauna and Dangari. Residents of Kwatsal village reportedly billed N4million were said to have already paid N2million out of the money to the bandits. The report was corroborated by the member representing the communities in the state House of Assembly.

To interrogate this menace of banditry, I have in the past three years been to Katsina, Kaduna, Kebbi and Sokoto. Following the invasion of Tabanni, Allikiru, Gaidan Kare, Kursa, Dankilawa, Ruwan Tsamiya and Gidan Barebari villages in Rabah Local Government of Sokoto State in 2018, I visited survivors who shared with me their harrowing experiences at the hands of killer-bandits. I spoke with Muhammadu Mani, a farmer who survived the brutal onslaught that left 32 persons murdered by invaders who came in a convoy of about 50 motorbikes carrying as many as three persons, all wielding guns and other assault weapons. “We could hear these men saying, ‘Let us kill all their men and see whether their women alone can bear children’”, recounted Mani.

What confounds is that rather than confront them, what we hear from federal government officials are excuses. The Attorney-General of the Federation and Justice Minister, Abubakar Malami, SAN, argues for striking “a balance between constitutional presumption of innocence and evidential proof of reasonable ground for suspicion in making disclosures” about certain categories of criminals for which “Naming and shaming of suspects is not embarked upon as a policy by the federal government.” But he does not apply this same principle when dealing with other criminal groups. Also, in May this year, Information and Culture Minister, Lai Mohammed stated that the prosecution of bandits and kidnappers is not the responsibility of the federal government because, according to him, “these are not federal offences”, even when every security agency is controlled by the federal government.

In recent weeks, international media focus has been on Nigeria amid genuine concerns that the challenge posed by these criminal gangs could push our country into becoming a failed state. From the Wall Street Journal to the Economist to Foreign Policy to The Guardian of London, they all remark on the weakness of our military/security institutions vis-à-vis the growing strength of bandits. Yet, as I stated in my speech at the Lagos State Chapter of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ) lecture last week, we have dragged the military to restore law and order which is primarily within the purview of the police. We now deploy troops to guard key installations, quell civil disturbances, man roadblocks, combat banditry, armed robbery and kidnappings as well as provide security for the conduct of elections.

I sympathise with the military that must now take the blame for systemic mismanagement of the security sector that has led to their playing roles constitutionally meant for others. In the process, they have attracted the usual contempt that comes with familiarity, despite their enormous sacrifices in the past decade. Ultimately, the challenge of national security is the responsibility of political leadership. By allowing officials to speak at cross-purposes on the menace of banditry and in the absence of appropriate responses, a needless suspicion has been created in the minds of many Nigerians in a manner that helps the bandits and jeopardises any efforts to confront them as a national imperative. For the umpteenth time, I join the National Assembly and other stakeholders to encourage President Muhammadu Buhari to arrest this dangerous drift before it is too late.

The Yar’Adua Study on Subsidies (III)

Last Friday in Abuja, the Partnership to Engage, Reform and Learn-Engaged Citizens Pillar (PERL-ECP) brought critical stakeholders together for a dialogue on fiscal governance in Nigeria. In his opening remark, Adiya Ode, team leader of the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office funded programme, said Nigeria “has a dubious honour in topping many of the negative HDI charts ranking alongside countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, and D.R, Congo who have experienced devastating wars.” He added that even if we discount the general insecurity in the country, “service delivery especially in health and education, is stagnated.” But the situation is not hopeless. Nigeria, Ode also argues, “has sufficient resources to give its citizens a decent living if the governance blockages can be fixed.”

To promote conversation on the way forward along this direction, I began this series two weeks ago by examining the report of a study conducted by the late President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua on subsidies in five sectors (power, education, health, agriculture, and petroleum). I continue today with the report on subsidy in the health sector. But as I previously stated, although the 13-year-old report is mostly presented by charts and bullet points, I have turned it into a flowing narrative.

Nigerian healthcare problems are dominated by communicable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, diarrhea etc. Natural and premature morbidity is high, as are anemia and vitamins and macro nutrient deficiencies. Thus, the country’s health profile is widely seen as requiring a significant continuing role for public interventions.

Globally, health financing schemes include user charges, health insurance, budgetary allocations under free health system and a combination of these methods. The federal government has made some attempt to protect the poor from unaffordable health care fees. Specifically, the treatment of some communicable diseases, HIV/AIDS and some specialized immunization has been provided free to patients and children. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that these facilities are universally provided and not targeted at the poor only.

Statistics from the federal ministry of health reveal that subsidies were paid to 23,601 hospitals, 71,930 hospital beds and 35,215 physicians in 2001; 25607 hospitals, 72600 hospital beds and 38355 physicians in 2002; 23618 hospitals, 73230 hospital beds and 40159 physicians in 2003; 23641 hospitals, 73680 hospital beds and 41935 physicians in 2004 and 24522 hospitals, 85523 hospital beds and 42563 physicians in 2005. The government-run insurance scheme covers active public servants and their dependents as well as some informal independent workers in public and private facilities. The scheme is financed through a 5.0 per cent levy on the basic salaries of all government workers, while the employer pays 10.0 per cent monthly. An area of concern in the Implementation of subsidies in health is the absence of clear policy on exemptions and waivers.

A breakdown of expenditure in health services by the federal government showed the dominance of spending on tertiary and secondary healthcare services. In 2000, this accounts for N20.5 billion, representing 2.9 percent of total expenditure and 0.4 percent of GDP; in 2001, it accounts for N44.6 billion, representing 4.4 percent of total expenditure and 0.8 percent of GDP; in 2002, it accounts for N63.2 billion, representing 6.3 percent of total expenditure and 1.1 percent of GDP; in 2003, it accounts for N39.7 billion, representing 3.2 percent of total expenditure and 0.4 percent of GDP; in 2004, it accounts for N52.4 billion, representing 3.7 percent of total expenditure and 0.5 percent of GDP; in 2005, it accounts for N77.5 billion of total expenditure and 0.5 percent of GDP; in 2006, it accounts for 94.5 billion, representing 4.9 percent of total expenditure and 0.5 percent of GDP and in 2007, it accounts for N50.7 billion, representing 2.1 percent of total expenditure and 0.2 percent of GDP.

Apart from high cost of health services delivery and low quality services, there are no adequate attempts to protect the poor from unaffordable health care fees. In the public health system, there is complete lack of efficient drug revolving financing systems. The limited coverage of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) remains a major obstacle to healthcare services for the poor. We can look at the examples of some countries.

CHILEAN MODEL: With a mixed healthcare system which has its provision and financing in the hands of both the state and private actors, the 1981 Act made health insurance mandatory for all sector workers who contribute 7 per cent of their payroll to either the public or private insurance schemes. This consists of: One large public insurer, the National Health Fund otherwise known as Fonds Nacional de Salud (FONASA), several competing private health insurers under the aegis of Institutuciones de Salud Provisional (ISAPRES) and traditional commercial indemnity insurance firms.

In FONASA, 40% of its financing need is through subsidies from the national treasury, while the remaining comes from the 7% contributed through beneficiaries’ payroll deductions and the co-payments made by patients in government health facilities. On the other hand, the ISAPRES is self-financed through the 7% payroll contributions from its beneficiaries and any additional voluntary contributions by some members. Another mode of financing for health in Chile is deploying user charges which has been operative in the country for more than two decades.

THAILAND MODEL: Low Income Card Scheme (LICS), Civil Servants Medical Benefits Scheme (CSMBS), Social Security Scheme (SSS), Voluntary Health Card Scheme (VHCS) and Commercial Private Health Insurance are some of the healthcare programmes. In terms of financing, about 60% of the Ministry of Public Health (MPH) hospital’s total revenue comes from government allocation and 40% from user charges. Special funds are set aside to compensate facilities for waived services. A budget is allocated to the provincial level and is financed through general revenue. The government of Thailand has used several criteria for allocating the LICS budget to provinces, including population, size, number of health facilities.

UK MODEL: The United Kingdom funds a strong social welfare safety net for its population that includes the National Health Service (NHS), a health system characterized by market-minimization and government ownership/control. General taxation funds approximately 80 per cent of NHS costs, 12% comes from national insurance contributions, 4% from patient fees, and 4% from miscellaneous sources. The UK National Insurance contributions additionally require employees to pay10 per cent of their weekly taxation income between GBP 87- 575 and employers to pay 11.9% payroll tax for earnings over GBP. Hospitals are generally funded from a global budget.

LESSONS FOR NIGERIA: We can learn from the implementation of protection mechanism for the poor in Chile that has reached all the poor through FONASA. When designing protection mechanism, careful consideration must be given to who determines eligibility and possible incentives for the contributing richer population. The model of LICS in Thailand could be adopted as it allows the poor free access to medical services. Equally, special fund should be set aside from the budget to reimburse facilities for waived services. Example from UK shows that the government has a dedicated account for health financing, with 17.5 of VAT receipts dedicated to health fund. Designing and implementing exemptions is considerably simpler than doing so with waivers.

A system of exemptions requires one initial basic decision namely determining which services will be offered for free or at an extremely reduced cost. In addition, the design should entail who will deliver the exempt services. Designing and implementing a system of waivers is, in contrast, considerably more complex because it imposes the adoption of different rules for different individuals.

ENDNOTE: In the World Health Organisation (WHO) ‘Best Healthcare in The World 2021’, Nigeria is ranked in number 144 among 167 countries, and below several African countries like Liberia, Togo, Guinea, Zimbabwe etc. In fact, Nigeria is ranked above only African countries like Chad, Niger, Somalia, South Sudan, and Eritrea. Questions to ask therefore include why is there high reliance on out-of-pocket (OOP) payments as a means of financing healthcare in Nigeria with 98 percent of population living without health insurance? What is responsible for the high communicable diseases burden, rising incidence of non-communicable diseases as well as elevated rates of infant and maternal mortality? What has happened to all the various national health plans and other policies that have been enacted for the growth of the healthcare sector in the country?

In 2001, Nigeria hosted Heads of State of member countries of the African Union (AU) where the leaders pledged to commit at least 15 percent of their annual budgets to improving their health sector. Since that commitment was made, Nigeria has not for once achieved even a half of the benchmark. How then can people of low-income have access to healthcare if they cannot afford it from their pockets? And how then can we expand the reach of medical services to cover more people without drilling holes in their pockets? And given the foregoing situation, do we then understand why our doctors are fleeing the country with the attendant consequences on our health sector?

Meanwhile, despite a strong leftist background as a disciple of the late Mallam Aminu Kano, the late President Yar’Adua had, by 2008, become convinced that subsidies, especially in the petroleum sector, were mere avenues for transferring public money to rent seekers. But he was also concerned that opposition by Organised Labour was based on the unsustainable argument that fuel subsidy benefited the poor and that Nigeria had enough resources to keep it going. When his Chief Economic Adviser, Mr Tanimu Yakubu Kurfi and Finance Minister, Dr Mansur Muhtah completed their first assignment of interrogating subsidy in the petroleum sector, the president constituted another small team to examine subsidy in four other sectors (Power, Education, Health and Agriculture) to see whether they were well-targeted. Highlights from the study is what I have been publishing in the past two weeks beginning with Power and Education (last week). With the foregoing report on Health, the next one will be on subsidy in Agriculture before I end the series with the petroleum sector. However, my friend, Bolaji Abdullahi, former Sports Minister who also held the Education portfolio as a Commissioner in Kwara State, has waded in on how we can begin to rethink funding the Education sector in Nigeria. I will run his intervention next week while the conversation continues.

PART ONE: https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2021/10/14/the-yaradua-study-on-subsidies-1/

PART TWO: https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2021/10/21/the-yaradua-study-on-subsidies-ii/

Aig-Imoukhuede and Civil Service Reform

Shortly before the closing plenary at the 27th Nigerian Economic Summit in Abuja on Tuesday, I moderated a signing ceremony between the Office of the Head of the Civil Service of the Federation (OHCSF) and the Aig-Imoukhuede Foundation. Mr Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede and Dr Folasade Yemi-Esan agreed to commence implementation of the Enterprise Content Management Solution (ECMS)—a public-private collaboration digitalisation project aimed at driving public sector reform in Nigeria.

As a member of the Advisory Board of the African Institute for Governance (AIG), a subsidiary of the Aig-Imoukhuede Foundation chaired by President Olusegun Obasanjo—which annually awards scholarships to six Nigerians and Ghanaians to study at the Oxford University Balvatnik School of Government—I am aware that this idea was consummated in 2017 when Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, SAN (who witnessed Tuesday’s event) facilitated the partnership between the OHCSF and AIG for development of an action plan that builds on the Federal Civil Service Strategic Plan 2017-2019. Since then, the Aig-Imoukhuede Foundation has been working with the OHCSF, providing necessary consulting support and funding for the full implementation of the ECMS in stages.

Meanwhile, the focus of the Aig-Imoukhuede Foundation as a philanthropic organisation has been on transforming the civil service across the continent but specifically in Nigeria for efficient service delivery. The idea is to develop programmes and mobilise resources to build the capacity of public sector leaders while also promoting public-private sector partnerships. The foundation works with government ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs), academic institutions, civil society, and private sector entities by providing financing for capacity building and advocacy.

Given how huge the task of revamping the public service in Nigeria is, I have likened what Aig-Imoukhuede is trying to do to that of a young girl who, walking along a beach where thousands of fish had been washed up, decided to pick and throw them back into the ocean one after another. She had done this for some time when a man approached her and said, “Little girl, look at this beach and the number of fishes here. What you are doing makes no difference.”

The girl seemed crushed but after a few moments, she bent down, picked up another fish, and hurled it as far as she could into the ocean. Then she looked up at the man and replied: “I have made a difference to that one.”

Such stubborn resilience will serve Aig-Imoukhuede and wife, Ofovwe, as their Foundation proceeds with its mission to reform an institution where some senior officials propose seeking a $200 million loan for the country to “medically fight malaria”!

• You can follow me on my Twitter handle, @Olusegunverdict and on www.olusegunadeniyi.com