By Enyichukwu Enemanna

The year 2024 came with a new wave of voter anger and probably a little more coordinated opposition politics, which saw a record five sitting governments across Africa lose power to their opponents. The only time such a wave of opposition takeover blew on the continent was some time in 2000, and it was four. Incidentally, Ghana was among them when John Agyekum Kufuor of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) won the presidential election, defeating John Atta Mills of the ruling National Democratic Congress (NDC), marking the first time Ghana recorded a peaceful transfer of power.

In the same year also, Abdoulaye Wade of the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS) won the presidential election in Senegal, defeating incumbent President Abdou Diouf, who had been in power for 19 years. Also, in Côte d’Ivoire, Laurent Gbagbo of the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) won the presidency after defeating Robert Guéï, a military ruler who tried to forcibly cling to power despite losing the election. This did not end without political unrest that led to the loss of lives and property estimated at billions of dollars.

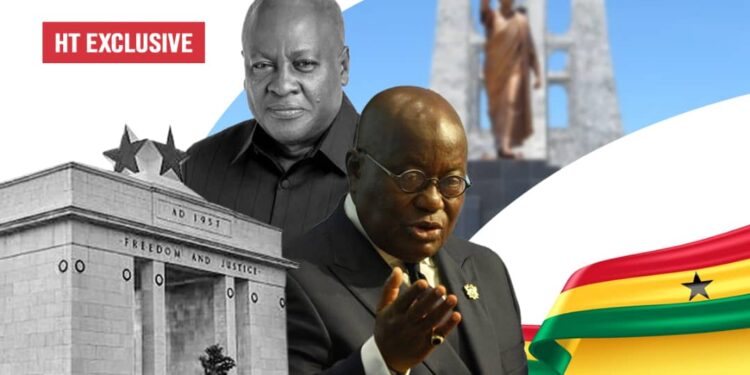

With the victory of John Dramani Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) who defeated the Vice President and the candidate of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), Mahamudu Bawumia, Ghana joins the league of countries like Botswana, Mauritius, Senegal, and the self-declared republic of Somaliland where, in the last 12 months, the sitting government has been shown the exit door.

In the case of Ghana, the country’s electoral commission declared Mahama, who was in office from 2012-16, the winner of the December 7 presidential poll with 56.55% of the vote. The defeat of NPP may not have come as a surprise to keen political observers. Opinion polls ahead of the election had pointed to the disenchantment of citizens against President Nana Akufo-Addo and his government. Again, since the return of multi-party politics in the country in 1992, the NDC and the NPP have alternated power, and none of the parties has ever won more than two consecutive terms in office.

Economic Downturn, Hunger in Election Year

The defeat of the governing NPP in Ghana spans from a number of factors, bordering on bad economic shape, corruption, and collective intolerance of citizens against a government that has woefully failed to address growing poverty, hunger, and depravity. The cocoa and gold-rich country has been in economic crisis since 2022 when it sought assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be able to meet its payments to the rest of the world and restore the health of government finances. This was also the second time in the three years that Ghana sought “salvation” at the doorstep of the IMF and the 17th since independence in 1957, all happening under the NPP government.

Inflation also peaked, hitting 54% some time in 2022, while the local currency, the Cedi, failed to stabilize as value reduction continued. From January to November 2024, monthly consumer inflation figures averaged 22.85%, far below the pre-crisis period (2017-2021) when it was 10.14%. According to a report by the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE), the major issues that were of concern to the Ghanaian voters were the economy, jobs, education, roads, and infrastructure provision. Others include addressing the illegal gold mining, popularly referred to as galamsey, health, agriculture, and addressing corruption. The key concern on the economy is the declining living standards.

“I’m so excited for this victory,” Salifu Abdul-Fatawu told the BBC in the central city of Kumasi. He said he hoped it would mean that he and his sibling would get jobs, while the price of food and fuel would come down.

Also, an NPP supporter whose name was given as Nana accepted that “my party is NPP, but whatever they did was not good. The system was so bad in an election year, and so most people were not happy.”

Mahama’s first term in office was, though, marred by an ailing economy and frequent power outages, but Ghanaians are hopeful that his second missionary journey will usher in a change. They probably got less than they had bargained under NPP and couldn’t wait to send the party home. During the campaign, Mahama promised to transform Ghana into a “24-hour economy.”

The President-elect, who will be sworn in on January 7, has also promised to press for a review of the $3 billion rescue package from the IMF, reduce wasteful spending, and increase investment in the country’s energy sector. “When I talk about renegotiation, I don’t mean we’re jettisoning the programme,” Mahama, who has earlier stated his intention to renegotiate the IMF programme secured by the outgoing President Nana Akufo’s government in 2023, told Reuters recently. “We’re bound by it, but what we’re saying is within the programme, it should be possible to make some adjustments to suit reality.”

In Botswana, Ruling BDP Humbled After 58 Years

One of the greatest shocks in Africa’s political world in 2024 is the defeat of the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which had for nearly six decades dominated the political scene in the Southern African country, winning each cycle of elections, even under controversial circumstances since the country’s independence in 1966.

An opposition coalition under the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), led by lawyer Duma Boko, thwarted President Mokgweetsi Masisi’s bid for a second term in office. Like Ghana, poor handling of the economy and a skyrocketing unemployment rate ended BDP’s 58-year rule. Analysts also alluded to economic grievances, particularly among young people, for the downfall of the BDP in the country with a population of 2.5 million.

Like many African countries, Botswana’s economy has largely depended on the export of a single commodity – diamonds. A global downturn in the diamond market, however, caused economic growth to plummet this year to a projected 1%, while unemployment rose to 28%.

On the contrary, Botswana’s GDP per capita was $7,250 in 2023, compared with an average for sub-Saharan Africa of $4,800, World Bank data indicates. This also, to an extent, shows prudence in the management of the country’s commodity windfall, as much investment has been made in health, education, and social welfare.

Even in the parliament, the governing BDP had a rough day as it lost several of its seats to the opposition, winning only six in the 61-member Assembly, from its previous 38. The Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), on the other hand, got more than the 31 required to emerge the majority, elect the President, and then form the government.

The defeated Masisi accused his party of getting it wrong. The party “had got it wrong big time,” Masisi told a press conference. “I will respectfully step aside and participate in a smooth transition process ahead of inauguration. I am proud of our democratic processes, and I respect the will of the people.”

Shortly after his election into parliament, Kgoberego Nkawana told reporters that many young people in Botswana remained jobless despite huge deposits of diamonds and a fairly thriving tourism industry in the country. “The unemployment rate is very, very high, and people are living literally on handouts from the government because there are no jobs. So it’s really bad,” Nkawana said.

Another interesting note from Boko’s victory is, despite founding the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) way back in 2012, he never secured victory despite trying three previous times. He realized the power of coalition, which eventually removed the BDP, the only party anyone from 58 years and below has known as the party in power. It is heartwarming to note that the UDC has committed to creating 450,000 to 500,000 jobs within five years.

The People Won in Mauritius, Senegal, and Somaliland

In Mauritius, a coalition saw a two-time former Prime Minister and opposition leader, Navin Ramgoolam, return to power under the platform of the Alliance of Change (ADC). He triumphed over Pravind Jugnauth of the Militant Socialist Movement (MSM), who had been in power since 2017. His party also lost gallantly in the National Assembly as the opposition ADC grabbed 60 out of the 62 seats.

During the campaign, both camps promised to improve the lot of Mauritians who face cost-of-living difficulties despite robust economic growth. The ADC outlined measures, including the creation of a fund to support families facing hardship, free public transport, increased pensions and reduced fuel prices, as well as efforts to tackle corruption and boost the green economy in its manifesto.

In Senegal, there was also a political turnaround in a way not expected by the ruling party. Just weeks ahead of the election, the main opposition leaders Bassirou Diomaye Faye and Ousmane Sonko were languishing in jail as the government of President Macky Sall detained them under trumped-up charges, fearing defeat at the polls over their popularity among young people.

After growing domestic and international pressure led to Faye and Sonko being released, Faye went on to win the presidency in the first round of voting, with the government-backed candidate winning only 36% of the vote following the disqualification of Sonko.

In the self-declared Republic of Somaliland, the opposition candidate, Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi “Irro” of the Waddani (National), secured 63.92% of votes to defeat the incumbent President, Muse Bihi Abdi, who won 34.81%. The territory declared independence in 1991 but has never achieved international recognition. Despite this, Somaliland has a functioning government and institutions, a political system that has allowed democratic transfers of power between rival parties, its own currency, passport, and armed forces. The new President says he will pursue international recognition for the territory, which Somalia says is its breakaway.

These trends in the past year in the African political firmament indicate a higher democratic resilience, which most times is often dwarfed by dictatorship, sit-tight syndrome, and politically motivated unrests that have sometimes blossomed into full-scale civil war in some African regions.

In Namibia, for instance, the credibility of the November presidential election in which the governing party, SWAPO, that has been in power since Independence in 1990, retained power has come under serious scrutiny. With the presidential candidate Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah being declared the winner in the poll characterized by a shortage of electoral materials that led to a 3-day extension in some regions, Namibia produced its first female President and will be joining Tanzania in the list of African countries where women are calling the shots.

But despite the irregularities, SWAPO lost 12 of its parliamentary seats to the opposition, dropping from 63 to 51, the worst parliamentary defeat since 1990. Panduleni Itula, the presidential candidate of Independent Patriots for Change (IPC), which won 20 seats in the 96 elected members’ Assembly, has since rejected the outcome of the election. His party has said it would “pursue justice through the courts” and has encouraged people who felt that they had been unable to vote because of mismanagement by the electoral commission to go to the police to make a statement.

For the first time since 1991, when the white dominance was ended, South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) failed to secure 50% of the vote in a national election. This forced President Cyril Ramaphosa, who was gunning for a second term, to enter into a coalition government, giving up 12 cabinet positions to other parties, including powerful positions such as home affairs. Corruption, the economy, and infrastructure, especially power, were all at the forefront during the election.

This was not peculiar to Africa alone. Popular discontent over inflation played a role in the defeat of Rishi Sunak and his Conservative Party in the UK. Also, Donald Trump made a shocking comeback to the White House after he defeated the Democratic candidate, Kamala Harris, who was still sitting as Vice President. Against all odds, Trump secured a second non-consecutive term, the second person to achieve the feat in the history of the US.

As 2025 sets in, it is hoped that voters across Africa continue to give non-performing leaders a bloody nose for taking them for granted, just like Ghana, Botswana, Mauritius, Senegal, and Somaliland did in the outgoing year. Despite myriads of challenges, democracy in Africa is taking deeper root. The credibility of electoral bodies and non-interference in the system is the bastion toward consolidating the gains achieved in the 2024 political calendar.