By Ebi Kesiena

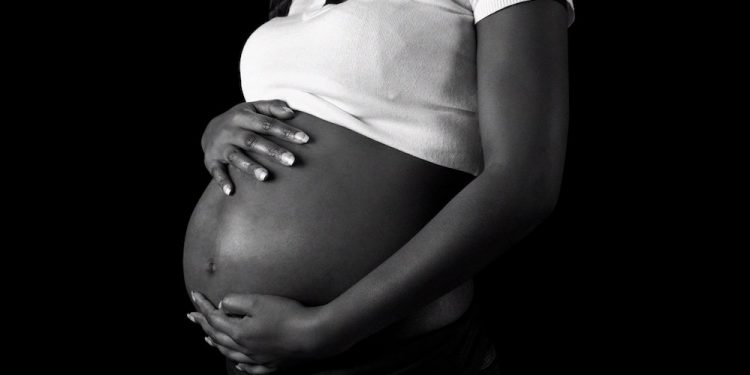

A report released recently by the non-profit Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) estimates that seven women and girls die every day in Kenya due to unsafe abortions.

In the Dandora slum in the eastern suburbs of Nairobi, where Victoria Atieno works with the Coalition of Grassroots Women Initiative, sanitation workers sometimes find abandoned foetuses in the neighbourhood’s huge garbage dump.

Volunteers tasked with cleaning up the Nairobi River in 2019 retrieved 14 bodies from its trash-clogged waters, most of them babies.

Many women will do anything to avoid that fate, from drinking bleach to using knitting needles or clothes hangers to end their pregnancies.

The results are horrific, ranging from ruptured uteruses, cervical tears, and vaginal cuts to severe infections, bleeding, and death.

Kenya’s constitution eased access to abortions in 2010, but entrenched stigma about the procedure means that many women resort to traditional practices or backstreet clinics which put their life in jeopardy.

Kenya’s constitution says abortions are illegal unless “in the opinion of a trained health professional, there is need for emergency treatment, or the life or health of the mother is in danger, or if permitted by any other written law”. No other conditions or terms are spelt out.

The vaguely worded document puts decision-making power wholly in the hands of health providers.

So when the health ministry stopped training abortion providers in 2013, access to such services took a hit, and women bore the brunt. Every week, 23 women die from botched abortions which campaigners say the real number is even higher.

The ministry’s move came a year after its own study warned that a “disproportionately high” number of women were dying in Kenya because of unsafe abortions.

According to Martin Onyango, CRR’s Senior Legal Adviser for Africa, Kenya’s constitution stating that abortions are illegal was not based on scientific evidence.

Ministry officials declined interview requests, with a reproductive health expert in the ministry telling the press that they are not permitted to talk about abortion at all.

The ministry was pulled up by the Nairobi High Court in 2019 for violating women’s and girls’ rights to physical and mental health by halting training for legal abortion providers.

As these abortions are extremely difficult to access at state hospitals, some private health providers perform the procedure, for which the fee starts at around 3 000- 4 000 Kenyan shillings ($27 / 23.5 euros). Pills are used to curtail shorter-term pregnancies.

For women who turn to these sources, fear of disapproval and shame can run deep. The silence lingers even in doctors’ waiting rooms.

In Dandora, as rape survivor Seline awaited the results of a pregnancy test, she had little doubt about what to do next.

Barely surviving on a monthly wage of 5,000 shillings, the 38-year-old domestic worker told AFP she was determined to get an abortion if the test was positive.

“If the hospital refuses, I will do it the traditional way, with herbs. I am ready to do anything, as long as I don’t have to have this baby.” she said.