By John Ikani

Malians are heading to polls to participate in a crucial referendum to voice their opinion on the constitution presented by the ruling junta.

The proposed constitution has sparked speculation about the intentions of the country’s strongman leader, who may seek election.

Since a military coup in August 2020, Mali has been under military rule due to a decade of instability marked by jihadist insurgencies, political turmoil, and economic crises.

Approximately 8.4 million eligible citizens have the opportunity to vote either “yes” or “no” on the draft constitution.

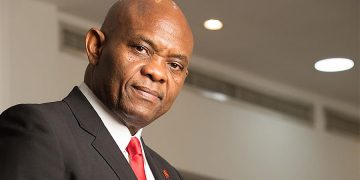

The electoral test will serve as a gauge for Colonel Assimi Goita, the 40-year-old leader, who has pledged to return the country to civilian rule in the 2024 elections.

Voting will commence at 0800 GMT, and the results are expected to be announced within 72 hours.

However, voter turnout has historically been low in Mali, a country with a population of 21 million.

Many citizens have grown weary of chronic instability, while others face the direct threat of jihadist attacks in the central and northern regions.

Security remains a pressing concern, with a constant risk of attacks.

Consequently, certain parts of the country, including Kidal, the ex-rebels’ stronghold in the north, will not be able to hold the vote.

The junta’s ability to restore stability and the level of public enthusiasm for its agenda will be judged based on the voter turnout.

The junta has presented the new constitution as a solution to Mali’s ongoing crises.

The nation’s troubles began in 2012 when separatist insurgents in the north, feeling marginalized by the southern government, aligned with Al-Qaeda-linked Islamists and seized large territories.

France, the former colonial power, intervened and helped push back the Islamists.

However, attacks have persisted, leading Bamako to sever its alliance with Paris in favor of Russia and its Wagner mercenaries.

In March 2020, disputed parliamentary elections and mass protests against a government unable to address the insurgency, corruption, and economic crisis culminated in a coup.

Goita initially appointed an interim president but later ousted him in a second coup in 2021, assuming the top position himself.

Concerns have now emerged regarding his commitment to stepping down next year.

In a significant move, Mali’s ruling junta called for the immediate departure of the country’s UN peacekeeping mission, which has played a central and controversial role in the security crisis, resulting in the loss of nearly 200 peacekeepers’ lives over the past decade.

The military rulers have progressively imposed operational restrictions on the peacekeepers and ultimately labeled the mission a “failure” and part of the problem.

If approved, the new constitution will grant greater powers to the president, including the authority to hire and fire the prime minister and cabinet members.

The government will be accountable to the president rather than parliament, as stipulated in the current 1992 constitution.

The proposed constitution also includes amnesty for individuals involved in previous coups, reforms in the regulation of public finances, and the requirement for MPs and senators to declare their wealth to combat corruption.

Opponents of the new constitution, including former rebels, imams, and political adversaries, have voiced their strong opposition.

Influential religious organizations oppose the continuation of secularism, a principle enshrined in the existing constitution.

Former rebels in the north, who have signed a significant peace agreement with the state unlike the jihadists, also reject the proposed constitution.

Critics argue that Mali needs a system built around institutions rather than centered around an individual.

Despite the vocal opposition, observers predict a majority “yes” vote. Malians are dissatisfied with past presidents from democratic regimes and the escalating level of corruption.

They seek a change from the status quo. However, low voter turnout is widely anticipated, as Malians have historically shown limited enthusiasm for participating in elections, with turnout rarely surpassing 30% since 1992.