By Enyichukwu Enemanna

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), every human being has the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The right to health and other health-related human rights are legally binding commitments enshrined in international human rights instruments.

WHO in its Human Rights Key Facts also says governments have the constitutional obligation to develop and implement legislation and policies that guarantee universal access to quality health services and address the root causes of health disparities, including poverty, stigma and discrimination among citizens.

The point 5 of the Key Facts published December 1, 2023 also declared that Universal Health Coverage (UHC) grounded in primary health care helps countries realise the right to health by “ensuring all people have affordable, equitable access to health services.”

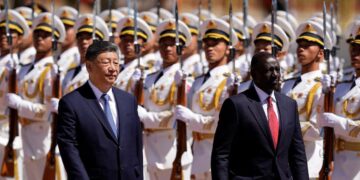

African leaders have however consistently attracted criticisms for neglecting the health system in their countries while embarking on medical tourism outside the continent, mainly in Europe, North America and Asia.

A social commentator based in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, Calistus Uwakwe attributed the “insatiable” desire for overseas medical care to lack of confidence in the African system by the leaders.

“It’s well documented that politicians from across the continent go abroad for medical treatment. The reasons for exercising this choice are obvious: they lack confidence in the health systems they oversee, and they can afford the trips given that the expenses are paid for by taxpayers.

READ ALSO: Nigeria: Despite Unstable Power Supply In 2023, Discos Raked In Over N1trn Profit

“The result is that they have little motivation to change the status quo. Medical tourism by African leaders and politicians could therefore be one of the salient but overlooked causes of Africa’s poor health systems and infrastructure.”

Exporting Money And Patients

Professor Khama Rogo of the World Bank had in an interview with the media in 2016 posited that despite being resource constrained, Africa spends so much money in search of medication abroad instead of developing its own capacity. As far back as 2015, World Bank statistics indicated that Africa lost over $1billion a year on medical tourism abroad.

In 2015, Grace Ssali Kiwanuka of the Uganda Healthcare Federation told reporters that her country loses at least $3 million yearly to medical tourism, an amount she believes is highly conservative because there is no dedicated body to check who goes out on medical vacation.

“The figure could be higher as there is no central body that co-ordinates who goes out. Health insurance companies that give international benefits make direct payments, there are individual using their own savings and then the numerous sponsors such as the Indian Association in Uganda that sponsors a number of people for heart surgeries,” she said.

Other accounts said in 2016, Africa spent over $6 billion on outbound treatment. In the same year, Dr Osagie Ehanire, Nigeria’s Minister of Health at the time, at the commissioning of a health facility in Jalingo, Taraba State North East Nigeria, said Africa’s most populous country alone spends at least $1bn annually on medical tourism.

Of particular interest is the involvement of leaders on the continent who do not only travel with elaborate entourages, but also travel in expensive chartered jets. It is estimated that in Uganda, the funds spent to treat top government officials abroad every year could build 10 hospitals.

In the case of Nigeria’s former leader, Muhammadu Buhari, multiple media sources noted that the cost of parking his presidential jet during his medical sojourn in London in 2017 was estimated at £360,000 – equivalent to 0.07% of Nigeria’s budgetary allocation for health in that same year.

All these speak to the inability of medical institutions around the 54 countries in Africa to handle the cases for which their leaders spend humongous amounts from national tills during such expensive medical tours. “Simply put, while the African health system is in depression and total ruins, the leaders find it fanciful to use their privileged offices to seek better health care services elsewhere,” Uwakwe noted further.

Death In Quest For Health

Some African leaders have found death on their journey to get health. Former Zambia leader, Levy Mwanawasa died in France in 2008 at the age of 59, just two months after suffering stroke. In August 2012, former Ethiopian Prime Minister, Meles Zenawi died at the age of 57 in a hospital in Brussels, Belgium, after contracting an infection in Belgium.

Also, long-time Zimbabwe leader Robert Mugabe died “peacefully” in Singapore at the age of 95 in 2019. It was not clear whether he passed away over cancer related complications or simply age.

Gabon’s former President Omar Bongo, the world’s longest serving head of government then died in a Spanish hospital at the age of 73. Bongo, leader of the west African country since 1967 before his passage had been receiving treatment for cancer for more than a month.

Another Zambian President, Michael Sata in 2014 died in London at the age of 77 where he was being treated in a private hospital for an undisclosed illness.

In 2012, Malam Bacai Sanha, the then President of Guinea-Bissau died at the age of 64 in a Paris hospital from a protracted and undisclosed illness, though it is thought to be related to diabetes. The list of political medical tourists who returned to their countries in coffin is endless.

Broken Promise

Former Nigerian leader Buhari had during the campaign that ushered him into power in 2015 promised to end medical tourism which his predecessors financed with state funds. However, this promised was observed in the breach.

He said government’s fund would not be spent on treating officials overseas, especially when Nigeria had the expertise. But amidst the brain drain in the medical sector, Buhari shortly after assumption of office in May 2015 went on his first medical trip to London, the United Kingdom eight months later, precisely on February 5, 2016 and spent six days.

His second medical trip according to media reports followed four months later on June 6, 2016. He spent 10 days treating an undisclosed ear infection after which he rested for three extra days before returning to Abuja on June 19, 2016.

In 2017, Buhari spent more time in the UK for medical treatment than he did in his own country. On January 19 of the same year, the then leader departed on his second longest medical trip. He returned to Abuja on March 10, 2017, spending 50 days away.

According to a national daily, in May of the same year, barely two months after his last trip, Buhari departed for London “for his longest medical pilgrimage lasting 104 days.”

He embarked on other countless medical trips to London before his tenure of office ended, including one of October 31, 2022 that lasted about two weeks. He returned to the country on November 13, 2022.

A right activitist, Olubunmi Michael faulted ex-President Buhari’s failure to erect a modern facility throughout his eight-year term that could bridge the gap in the number of Nigerians seeking treatment outside the country. “For a man who promised to end medical tourism, no single world class hospital in Nigeria is traceable to Buhari to cater for the needs of citizens who do not have the luxury of being treated abroad at slightest ailments with government funds. He did not only renege in his promises, he also betrayed the trust and goodwill that brought him to power,” he said.

Missed Opportunities

According to Ehanire, Nigeria alone accounted for $1 billion out of Africa’s estimated $6 billion on outbound treatment in 2016, making it the highest foreign healthcare spender. This humongous amount alone could be the game-changer the continent needs to fill the deficit in the health care system.

Africa also has a billion-dollar medical tourism market which could be accentuated with the involvement of the continent’s leaders through partnerships. This has however remained largely untapped.

Indian healthcare entrepreneurs and investors are already making significant in-roads into the continent by stamping their presence to dominate the market. Aggarwal Eye hospital and the Apollo Hospitals, both originating from India have presence in Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

Apollo Hospitals, believed to be India’s biggest healthcare chain, is investing in a $70 million, 500-bed hospital in Dar es Salaam. This multi-specialist facility is intended to serve patients and ‘would-be medical tourists’ in the East Africa region.

Another Indian medical company, Biohealth, is investing $5 million in a health facility on the continent for comprehensive cardiology diagnostics, dialysis, and radiology.

The COVID-19 outbreak which imposed movement restrictions presented opportunity for countries, regions and continents to search inwards and develop strategies aiming to enhance their health care system. African leaders were caught napping as the medical tourism continues, gulping billions of dollars in funds.