By Olusegun Adeniyi

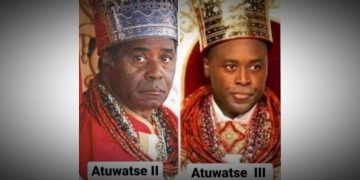

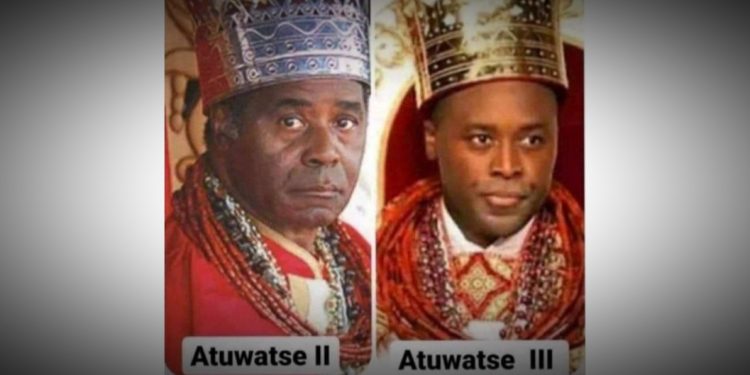

Despite the five-hour time difference between Boston and Warri, I followed last Saturday’s coronation of Ogiame Atuwatse III, the 21st Olu of Warri. That a blindfolded monarch picked that title (from the 20 ceremonial swords bearing the names of his predecessors) could not have been a coincidence. It is a testament to the courage of conviction exemplified by his late father, Ogiame Atuwatse II. I congratulate the Atuwatse III and the entire Itsekiri nation for how this story has ended.

At the Aghofen Palace ground in Warri on 30th November 2013, then Prince Tsola Emiko had joined his siblings (Nere, Toju, Ola and Neye) and their mother to publicly seek forgiveness from anybody their father (then just deceased) might have offended. His elder sister, Princess Nere Teriba who spoke on behalf of the royal family said on that occasion, “forgive him (Atuwatse II) if he had offended you. Find it in your hearts just to let it go. He blessed everyone. He never kept or harboured grudges against anyone. He kept us on our knees praying,” said the Princess who pledged support for their uncle who had been selected to succeed him. “I thank Iwere nation for honouring my father when he ascended the throne. Growing up as a young man, the elders and chiefs honoured and crowned him, even though he was not a conventional king.”

Many could not understand this act of grace from the immediate family of Atuwatse II, especially considering that the crown prince had just been denied the throne on account of where his mother hailed from. Besides, the Itsekiri people didn’t believe the late monarch did anything to warrant the forgiveness being sought by his family. In fact, the much-revered Igba of Warri, Chief Rita Lori-Ogbebor, was almost angry about it. “Obviously, the children are innocent and ignorant of the tradition. From the day he was crowned 28 years ago, Atuwatse II transformed from being just their father to being father of the entire Itsekiri nation.” She added that the Atuwatse II on whose behalf his children were apologizing was a great monarch who merely stepped on a number of big political toes.

Remarkably, the transition from Atuwatse II to Ikenwoli went without rancor. But with his death last December, there was a consensus among Itsekiri people that this time, Tsola Emiko should be the next Olu of Warri. Of course, there were also a few powerful chiefs who insisted on using a contentious 1979 military edict to rewrite history and the tradition of a Kingdom that began in 1480 with Ginuwa who reigned as the first Olu of Warri until 1510. At the end, the will of the people prevailed last Saturday.

Before I conclude with the substance of this intervention, let me take readers back to my column of 19th September 2013 on the late 19th Olu of Warri, Atuwatse II. Titled, ‘The Olu of Warri and His God’, there are embedded lessons that his son, Atuwatse III, may find useful as he begins what promises to be a long reign on the throne of his forebears.

“Henceforth, I submit and present the title ‘Ogiame’ to God, the creator, who made the sea and rules over all. Therefore, no Olu or person may bear the title or name that now belongs to God. I nullify all tokens of libation poured on the land and seas or sprinkled into the air in Iwere land. I frustrate all sacrifices of wine, blood, food, water, kola nuts and other items offered in Iwere land. In conformity with the new covenant, through the blood of Jesus, I release the royal bloodline, the chiefs of the Iwere kingdom, the Iwere people and land, waters and atmosphere of Iwere kingdom from all ties to other spiritual covenants and agreements.”

With the foregoing royal proclamation, the Olu of Warri, Atuwatse II, recently decreed a stop to some ancient customs of the Warri Kingdom after publicly renouncing the traditional name ‘Ogiame’. The Olu also vowed to replace all the rituals and practices that do not conform with his new faith in Jesus Christ. But the royal father did not have the last word on the matter as he met a stiff challenge from a cross-section of Itsekiri people who called for his dethronement. By the third day of what was almost becoming a violent protest, several youths and women had erected canopies and were cooking in front of the palace gate.

However, following the intervention of the Delta State Governor, Dr. Emmanuel Uduaghan, himself an Itsekiri man, the traditional ruler (who happens to be a staunch member of the Foursquare Gospel Church), had to annul his own decree for peace to reign. And with the crisis resolved, a thanksgiving service was held last Sunday with the crème-de-la-crème of the Itsekiri nation in attendance. Now that Uduaghan and other prominent Itsekiri sons have rallied to put out the fire that could have had far-reaching consequences in their ancestral land, a most pertinent question remains as to whether indeed the Olu could unilaterally reject the title ‘Ogiame’. This question is worth interrogating since what the royal father sought to jettison without due process were established values and deep-rooted beliefs of his people which have persisted over generations—traditions over which he was appointed to serve as custodian.

I find the Warri crisis fascinating because it speaks to the tension between Pentecostal Christianity and tradition, especially in our country. Richard Niebuhr’s highly revealing book, ‘Christ and Culture’, perhaps opens some window of understanding on this crisis. To demonstrate how Christians have attempted to deal with the challenge of their faith against the background of old beliefs and customs, Niebuhr identifies five approaches which he listed as: Christ against Culture; The Christ of Culture; Christ above Culture; Christ and Culture in Paradox and Christ the Transformer of Culture.

Unfortunately, the Pentecostalism that has been embraced in Nigeria today fits into the paradigm of ‘Christ against Culture’, a notion which rejects all the traditional African mores as archaic, backward, and evil. The presupposition is that those traditions belong to some sinister gods that need to be dropped for us to prosper materially and spiritually. For that reason, many Nigerian Christians have had to change their names based on the theology that those names were dedicated to some ancestral spirits whose yokes must be broken for them to be free from poverty, disease, and curse. While expressions of faith differ from one denomination to another, the preponderance of opinion among pastors is that our traditional heritages (sometimes including priceless artifacts, dating back to centuries) are hindrances to our faith as believers hence we must do away with them. It is within that context that we can situate the spiritual edict which got the Olu of Warri into trouble.

Now, I must make something clear: I am also a Pentecostal Christian—even with all my failings and imperfections—and I understand that one cannot serve the true God and still be worshipping idols. But I have problem with a faith that is expressed in symbolisms and even superstitions. For instance, I have listened to several songs and messages that the economic and political problems which plague our nation today can be traced to our hosting the 1977 Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) during which, as the tale goes, several countries came to dump their Satanic gods on our land. Not only do I believe there was nothing wrong in our hosting FESTAC, I see no correlation between it and the inability to harness our enormous potentials for the advancement of our society.

The Warri incident is instructive because there is a constitutional dimension to it which can be considered within the context of the Christian faith. The Olu for instance already has a Church within the palace and it is not on record that his people quarrel with that; so, the attempt to change the tradition under which he came to power is not only wrong but indeed self-serving. Like all positions of authority, there are sacred rules that bind the leader to the community and that explains why in other climes, Kings have been known to abdicate their thrones whenever there are irreconcilable conflicts between personal convictions (which sometimes include the love of certain women) and the traditional order.

In the case of Warri, the matter is even simple. If the Olu can demonstrate the true essence of the faith he professes and his subjects see the evidence in his deeds, perhaps he could gradually reform some of the traditions without the public drama that almost ended in hubris. The problem I see, however, is that such public profession of political Christianity has become the vogue. I have read of a minister who holds a strategic portfolio under the current administration in Abuja and doubles as the General Overseer of a Church he founded. Even if we choose to ignore the contradictions in such God-Mammon portfolio, questions must be asked as to whether the faith of this ministerial G.O. is reflected in his stewardship as a public official. What many fail to understand is that to develop our country and uplift our people, we need to burnish our cultural identity while adopting the instruments and methods of scientific civilization.

However, a fuller exploration of the issues will take us to the place of symbols in belief systems; the essential privacy of religion and indeed the tricky point of how all these intersect to sustain public order and social peace. To that extent, the peaceful resolution of the clash between the Olu of Warri’s private Christian belief and the imperatives of his public cultural symbolism as a traditional monarch speaks volumes to the rest of us. Religion as an aspect of culture thrives on symbols and rituals. Pentecostalism of course rejects the rites of the traditional Christian churches as it is founded on the redemption work of Christ on the Cross of Calvary. But I remain unconvinced that salvation is also a function of cultural suicide. For me, there is nothing that should preclude a traditional ruler from being a disciple of Christ as well as an authentic symbol of the culture of his people. This is the crux of a debate that is waiting to be inaugurated.

ENDNOTE:

I wrote the foregoing eight years ago and the monarch died two years later. In selecting his successor, the crown prince was bypassed reportedly on account of where his mother hails from. Meanwhile, the late Atuwatse II ascended the throne in 1987, eight years after the enactment of the edict that placed impediment on any aspiring Olu born by a mother not Bini or Itsekiri. The implication of that law against his crown prince (then just about two years old) could not have been lost on Atuwatse II, a legal practitioner who succeeded his own father. It was a perfect excuse (if any was needed) for him to marry another wife from Edo or Itsekiri to satisfy the ‘military provision’ on succession. That he chose not to spoke to his character. And going by the way his wife and children responded when the crown prince was denied the throne in 2015, it is also evident they were well grounded in the faith they profess. There was neither desperation nor expression of bitterness. Rather than go to court as it is most often the case with such matters in Nigeria, the children of Atuwatse II rallied behind their uncle who was given the throne. Six years later, Prince Tsola Emiko is now Atuwatse III.

While much song and dance have been made of the 1979 edict and the ‘missing crown’, they do not in any way invalidate the coronation of a new Olu of Warri. Nor do they detract from his legitimacy. There is a scene in Eddie Murphy’s timeless movie, ‘Coming to America’ that is instructive. After King Joffe Jaffa of Zamunda had forbidden his crown prince, Akeem, from marrying his American love choice, Queen Eoleon became angry with her husband. In trying to rationalize his decision, King Joffer said, “They could not marry anyway. It is against the tradition.” To this, the Queen replied, “Well, it is a stupid tradition.” The King mused: “Who am I to change it?” The Queen replied: “I thought you were the king.”

That tradition was changed, and the crown prince married his American wife.

We may say that is in the realm of fiction, but the reality also is that customs and traditions are not static, even within our environment. They evolve as the Awujale of Ijebuland, Oba Sikiru Adetona, reminded us in his 2010 autobiography. Aside unmasking many of the superstitions usually associated with coronation rites, the 87-year-old Ijebu monarch who ascended the throne 62 years ago (in 1959), wrote that “custom or tradition should not be dominating the people but rather, people themselves should be creating the traditions and customs according to their needs.”

That is what the Itsekiri chiefs have proved with the coronation of Atuwatse III which must be seen as a victory for married women in Nigeria who are not only discriminated against outside their ‘state of origin’ but are also often denied certain rights and privileges. And the moment Atuwatse III began the Christian praise worship song, ‘All the glory must be to our God, for He is worthy of our praise, no man on earth should give glory to himself…’ following his coronation, I knew the new Olu of Warri is his father’s son and the Itsekiri nation will be the better for it.

I have in recent days had interesting conversations with my host, Professor Jacob Olupona, NNOM, who teaches Indigenous African religions at Harvard Divinity School. A Christian himself, though of the Anglican denomination, Olupona believes that the first response of Atuwatse after coronation should have been to draw strength from his native spirituality and culture, rather than from a Christian song. But he also conceded that it reflects how deep faith played a role in this matter for the young monarch. “He probably believes his throne was saved by a Christian God of Justice who brought it back to him after six years. Whether we agree or not, there is a lot of theology there.”

However, Olupona enjoins the monarch not to make the mistake of discarding the myths, worldview, rituals, and values that may provide sacred canopy to his people because they have significant meaning. “Civil religion tradition such as the Warri’s Ogiemen story is not regarded as pagan but a unifying belief system that surpasses individual sectarian religion. Olojo in Ife is an example and so is Osun in Osogbo.”

Meanwhile, we must deal with the issue of discrimination against married women in Nigeria which presents itself in diverse forms. There have been situations in which a woman who has lived and worked for decades in the state of her husband suddenly finds that she cannot claim a position rightfully earned. In this instance, such denial of rights is being extended to her son. Yet, the notion of ‘indigene/settler’ dichotomy within a palace setting is indefensible and I hope Governor Ifeanyi Okowa will send an executive bill to the Delta State House of Assembly to nullify that repugnant 1979 edict, so that it no longer becomes an issue in future. To progress we must put an end to the warped politics of identity that has practically rendered Nigerian women married to men from states other than theirs practically ‘stateless’.

I do not know any member of the royal family, but I have followed their story since I first wrote about the 19th Olu of Warri in 2013. Speaking about his upbringing in a BBC interview, Atuwatse III said he grew up in a very normal household. “My parents ran a modern household with my father watching TV with his children. We lived a regular life except that we could notice palace activities.” Asked whether his late father trained him for the palace, Atuwatse III said no such thing ever happened. “Some chiefs and family members would say to me, ‘I hope you are watching and taking notes of this and that’ but my father never formally sat me down on my role,” said Atuwatse III.

I believe this was deliberate on the part of Atuwase II. He apparently wanted to build in his son the character required to navigate life without a sense of entitlement about the Itsekiri throne, even as a crown prince. He wanted his son to develop a sense of responsibility that would have him earn even what ordinarily should be his. That way, Atuwase II knew his crown prince would be prepared whenever duty called. It has paid off. When Prince Tsola Emiko was denied in 2015, he wholeheartedly supported his uncle. And when the throne became vacant last December and the selection process started again, he prepared himself for any outcome, including being overlooked. “I didn’t lobby for it; I didn’t manipulate the process but at the end, the same instrument that was used to deny me in 2015 endorsed me almost unanimously this time.”

There can be no better testimonial for Atuwatse III than the one given by Prince Yemi Emiko, a younger sibling to the immediate past Olu of Warri, Ogiame Ikenwoli. He is also uncle to the incumbent. Shortly after the choice was announced, Prince Yemi Emiko told reporters: “He (Tsola Emiko) was the most qualified. Stable character, strong mental capacity, clear understanding of the sensitivities of our people, deep, calculated thought processes, and skillful analytical mind on kingdom matters. There was simply no serious competition with him this time around.”

Long may Oguame Atuwatse III reign!

UN House Bombing: A Decade After

Today marks exactly a decade that the United Nations building in Abuja was attacked by Boko Haram suicide bombers. On that day, 19 dead bodies were recovered with scores of others seriously injured. One of them was Member Feese, a young woman from a remarkable family, who has refused to allow the tragedy to define her, despite the horrible experience and the visible (and other invisible) scars she still bears. To mark today in Abuja, there is a little ceremony at 1 Ebele Okeke Crescent, Wuye this evening to give limbs to three amputees.

Then a post-graduate student of Poverty and Development at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, Member was at the UN Office on 26th August 2011 to collect data for her dissertation on social protection in Nigeria when the terrorists struck. It is tragic that our security challenge has not abated. Nine years after two suicide bombers successfully attacked the Command and Staff College, Jaji, killing 11 people on the spot and injuring dozens, the Nigeria Defence Academy (NDA) was on Tuesday invaded by gunmen who killed two officers and abducted another who was also later confirmed dead. But this is an issue for another day.

Given a three percent chance of survival upon arrival at the London hospital where she was treated for life-threatening injuries in 2011, Member has today turned what started as a support network of friends and family members into an advocacy group that demands improved service delivery and more accountability, especially for the poor and marginalised of society.

For the past seven years, her initiative, ‘Team Member’—of which I am a board member alongside Mrs Aisha Oyebode, Mrs Angela Ajala, Hon Abike Dabiri-Erewa, Mrs Maryam Uwais and her mother, Mrs Nguyan Feese—has been working to establish a prosthetic center as a way of supporting amputees to become functional citizens and live with dignity. More importantly, Member, who works at the CBN, has been unrelenting in the advocacy for other victims that a normal life is possible, after such tragedies.

Despite having had her leg amputated from above the knee (because of the tragic incident), Member is able to handle her everyday needs without any qualms or complaints; driving herself to work during the week, traveling for official duties and generally doing what needs to be done efficiently, confidently, and competently. She therefore remains an exemplary role model for so many. For our society to develop, we need more shining stars like Member, who would exude the presence of mind and strength of character to convert personal tragedies to opportunities for helping others.

• You can follow me on my Twitter handle, @Olusegunverdict and on www.olusegunadeniyi.com