Tidjane Thiam, one of the world’s most brilliant financial executives, was ousted from his position as the chief executive of Credit Suisse, Switzerland’s second largest bank and a global icon. He was forced to resign over a sordid affair that he says he knew nothing about. What is the real story behind his ouster? Anver Versi reports

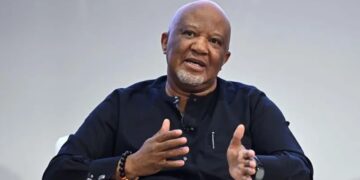

How the mighty are fallen. Tidjane Thiam, the Ivorian financial genius, ruled his world like a king until he was forced to resign as chief executive of one of the world’s most iconic financial institutions, Credit Suisse.

The news rocked not only Switzerland’s usually staid world of high finance, but made headlines around the globe. It was not just the passing – at least for the time being – of a financial colossus, it was the passing of perhaps the most unusual chief executive in the secretive, rarefied universe that is controlled by the legendary ‘Gnomes of Zurich’.

Tidjane Thiam was unusual in several ways. He had never worked in a bank until his appointment, in 2015, as the chief executive of Credit Suisse; he had not studied economics or anything to do with finance but maths and physics; he had not been raised and nurtured in the great house of finance but had cut his managerial teeth in the hurly burly of massive government projects in Côte d’Ivoire.

And he was a black African – a creature as unexpected and fabulous as the legendary unicorn in the world he came to inhabit with such presence.

Thiam was also a big man with a huge charisma in an atmosphere where having a low-key, discreet and almost self-effacing personality are regarded as desirable qualities. He spoke French, English and German. He was one of the highest-paid chief executives in Switzerland. He lived in a grand house with superb views of Lake Zurich. He entertained lavishly and with style.

He celebrated his African roots and made no attempt to become ‘Europeanised’ but by breeding and temperament he was cultured and sophisticated. Those who worked with him or got to know him say he exuded an aura of enormous charm as well as power. “He was one in a million,” said an investor in Credit Suisse following Thiam’s departure. “They can try but they cannot replace him,” he added.

Thiam first made headlines in Europe in 2002 when he was head-hunted by one of Britain’s biggest insurers, Aviva and rapidly promoted to the main board. A Francophone African in charge of Aviva’s European business? The British financial media did not know what to make of it. “Where is the catch?” someone asked.

There was no catch. In 2007, he was then poached by Prudential, a FTSE 100 listed company. More astonished headlines followed when he became chief executive in 2009 and began to turn the company around.

The $3 billion man

Some of the financial papers of the time wondered openly how someone from his background could fit into the rarefied atmosphere of the City, with its cliques, old school tie affiliations and the daggers hidden behind false smiles. They were waiting for him to fail.

He not only did not fail but his stock went up. In 2015, Urs Rohner, the chairman of Credit Suisse, arranged a series of meeting with Thiam and eventually persuaded him to leave Prudential and join the Swiss bank as its CEO. An hour after his appointment was announced, the company stock increased by 7.5%.

He became known as ‘the $3 billion man’ when he moved to Credit Suisse. This figure represented the rise in the value of Credit Suisse shares and corresponding drop in Prudential shares when his move was announced.

Credit Suisse, founded in 1856, was going through difficult times. It was embroiled in several international investigations for tax avoidance and had to pay around $2.6bn in fines. Its investment banking business was also struggling. Profits were down.

Rohner and the board knew they needed someone with the drive, strategic thinking and charisma to re-energise the institution and make it fit for purpose again. They looked around and spotlighted Thiam.

Thiam brought in some of this top lieutenants from Prudential, including Pierre-Olivier Bouée, who was to play such a pivotal part in the events that led to Thiam’s ouster, and made him his chief operating officer.

The relationship between the two went deep; they had met when both worked with McKinsey. Thiam had taken Bouée with him to first Aviva and later Prudential. At Credit Suisse, the Frenchman worked hand in glove with Thiam to bring about the 3-year restructuring of the bank that Thiam had planned and which resulted in the bank making a profit for the first time in four years.

The other pivotal character in the drama that was to unfold was the Swiss-Pakistani Iqbal Khan. Khan joined the bank’s wealth management division in 2013. Thiam had already identified wealth management rather than investment banking as the growth area so Khan became a key ally. He became CEO of the division in 2015 and according to the Financial Times, “he oversaw an 80% increase in divisional profit and helped bring in upward of $46bn in net new assets from 2016 to 2018”.

Khan, according to reports, was a popular young man among the staff – easygoing and always willing to help. Apparently, he was unaffected by hierarchy and tended to treat everybody, from the lowest ranks to the CEO and above, in an equal measure. Some saw him as the natural successor to Thiam when the time came.

Major storm brewing

However, while on the surface everything was smooth and positive, inside a major storm was brewing. Two years earlier, Khan had bought a house next to Thiam, demolished it and begun reconstructing it. Thiam, it is reported, was unhappy with the disruption and also because it blocked his view to the lake. He planted some trees to screen off the building works, leading to bitter squabbles including their respective wives.

In January 2019, Thiam hosted a cocktail party at his home; among the guests were Khan and his wife. Sometime during the evening, according to reports, the wives engaged in a furious quarrel. Thiam and Khan moved away but were also soon at each other’s throats, literally according to some guests. They had to be separated.

After this highly charged incident, which somehow found its way into the press, alarming the finance community which is terrified of any whiff of scandal, it became clear that Credit Suisse had become too small for both Thiam and Khan.

Khan sent out feelers among other banks and received positive responses from several. In July, he left Credit Suisse and joined arch rivals UBS as co-president of its wealth management division.

The alacrity with which UBS fast-tracked Khan was clearly founded on the expectation that he would bring some of his Credit Suisse clients, as well as staff, with him.

This possibility, as well as the fact that Khan continued to see some of his former colleagues – and with tens of billions at stake – raised red flags for Bouée. What was Khan up to?

Bouée, by his own admission, acted on his own. He hired a security firm, Investigo, to tail Khan and keep tabs on everyone he met. Soon detectives followed the banker wherever he went and made notes about everybody he met and talked to.

Bouée knew this was a no-no in the Swiss financial environment but, according to reports, private investigations go on all the time in the secretive world of Swiss finance. The important thing is to make sure that no one except yourself comes to know about it.

Unfortunately for Bouée and later Thiam, in mid-September, Khan found out that he was being tailed. From here, things turned ugly. During a shopping trip with his wife, Khan turned on one of the detectives, accused him of hounding him and photographed his licence plate.

There are conflicting reports about what happened next. Khan told the public prosecutor that the detective asked him to hand over his phone with the photo of the licence plate and when he refused, three men set about him, chased him and tried to take the phone by force. He shouted for police help and the detectives fled.

Falling on swords

The news of what had happened broke like a thunderclap over Zurich. Spies, chases, fisticuffs, compromising photographs! The media and the public licked their lips at the prospect of a delicious scandal developing. Credit Suisse, deeply embarrassed, worked to put out the flames.

The bank appointed a law firm, Homburger, to find out what had happened and who had ordered the surveillance. In the meantime, there was more shocking news. A contractor, named only as ‘T’, who had hired the detective agency, committed suicide. Things were going from bad to worse.

Early in October, the Homburger inquiry presented its report to the Credit Suisse board and said that Bouée had independently made the call to follow Khan. He resigned and was later sacked – although he has said since that he intends to sue the bank. The head of global security also resigned.

The Homburger inquiry also said it had not found any evidence that Khan had tried to poach any of the bank’s clients or staff. It also stated that there was no evidence that Thiam either approved of the spying or was aware of it before it became public in September.

The bank quickly distanced itself from the spying, saying that Bouée had “acted alone, and in order to protect the interests of the bank,” had ordered the spying on Khan, and he had not discussed the matter with Thiam or any other executives.

It also stated that “The Board of Directors considers that the mandate for the observation of Iqbal Khan was wrong and disproportionate and has resulted in severe reputational damage to the bank.”

But if the bank and Thiam thought that the line on the whole sordid affair had been drawn, another rude shock was in store. In December it was revealed that Peter Goerke, the former head of HR at the bank, had also been put under observation by Bouée. This was perhaps even more damaging as it implied a systemic use of private investigators by the bank. Credit Suisse’s reputation was in tatters. Too much damage had been done for anyone to be satisfied by only Pierre-Olivier Bouée falling on his sword. Other, bigger heads had to roll.

In the fever of anticipation and speculation that followed, it was clear that either Thiam or Rohner had to go. Both were damned by the law that said that if they didn’t know what was happening, they should have and that if they knew what was happening, they should have stopped it.

As speculation mounted, a number of the bank’s biggest shareholders came out solidly in favour of Thiam and against the chairman Urs Rohner. For example, David Herro, vice-chairman of Harris Associates, which owns 8.4% of the stock, later told the FT: “We don’t want to give up on Credit Suisse because they have a great franchise and they are so undervalued, but they have an incapable chairman, so we will take the steps to get him replaced… Urs is supposed to leave by 2021, but that’s not soon enough … to his already-poor track record, you can add removing a successful CEO.”

Other shareholders, including Silchester International and the US hedge fund Eminence Capital, also supported Thiam but the Credit Suisse board, after a marathon 20-hour session, decided that Rohner would remain in place and Thiam had to go.

Dignified to the last, Tidjane Thiam said he served at the board’s pleasure and if that was their decision, he would abide by it. But he had one sting in the tail. He presented his results as his last act as a chief executive of the bank. He said: “Our goal was to become a bank that generates profitable, consistent and quality growth. From 2016 to 2019, we expanded our wealth management business and generated net new assets of CHF121bn (€113.7bn), and our pre-tax profit from wealth management grew double-digit (+15%) for four years in a row, from €2.5bn in 2015 to €4.4bn in 2019.”

He ended by saying, “Our restructuring was a success and our performance in 2019, the first year after this restructuring, illustrates how much the bank has changed since 2015.”

Mission accomplished. Many, including Herro and other analysts have been asking if the same fate would have befallen him had he been a white European. He only said: “In Switzerland there are differences in how people feel about me. I cannot change who I am. I am right-handed. If people don’t like right-handed people, I am in trouble as I cannot become left-handed.” Enough said.

Given the results he has achieved, no wonder the shareholders have been livid at his ouster. But one chapter closes, another opens. We shall hear more about Thiam in the near future – of that there can be no doubt.

Read more on this story: Top Banker Tidjane Thiam ‘astonished’ by Black janitor act at party.

The post “Tidjane Thiam – Fall of a legend” first appeared on AfricanBusinessMagazine.